Giorgio Vasari applied more than one identity – usually two or four – to most of the figures in his fresco depicting the Marriage of Henry, Duke of Orleans, and Catherine de’ Medici.

In previous posts I revealed four identities to the moustached man placed at the shoulder of Pope Clement VII:

Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Duke of Milan

Giovanni Andrea Lampugnani, assassin of Galeazzo Maria Sforza

Alessandro de Medici, Duke of Florence

Gaston de Foix, Duke of Nemours, nicknamed The Thunderbolt of Italy

The central figure in the fresco, Pope Clement VII, bishop of Rome, is one of four identities. Not surprisingly two of them relate to previous popes: Clement I, and the anti-pope Clement VII (Robert of Geneva). The fourth identity connects to the two Roman mythology figures portrayed in the corner of the frame, Saturn and Ops. They parented five children, Jupiter being one of them, and it is Jupiter, representing the god of sky and thunder, who Vasari has embedded as the fourth identity.

Two symbols associated with Jupiter are an eagle and a lightening bolt. The latter connects to the identity of the head on Jupiter’s shoulder, Gaston de Foix, the Thunderbolt of Italy. As for the eagle, noted for its large hooked beak, we can recognise this feature in another identity given to the head on Jupiter’s shoulder, Galeazzo Maria Sforza.

The head of Jupiter can also be visualised as the head of a raptor, perhaps a bearded vulture, the red cape spread out like wings, and hands represented as claws digging into the arms of Henry and Catherine – or even the head of the bearded Jupiter as depicted in ancient statues of the chief deity of the Roman State religion.

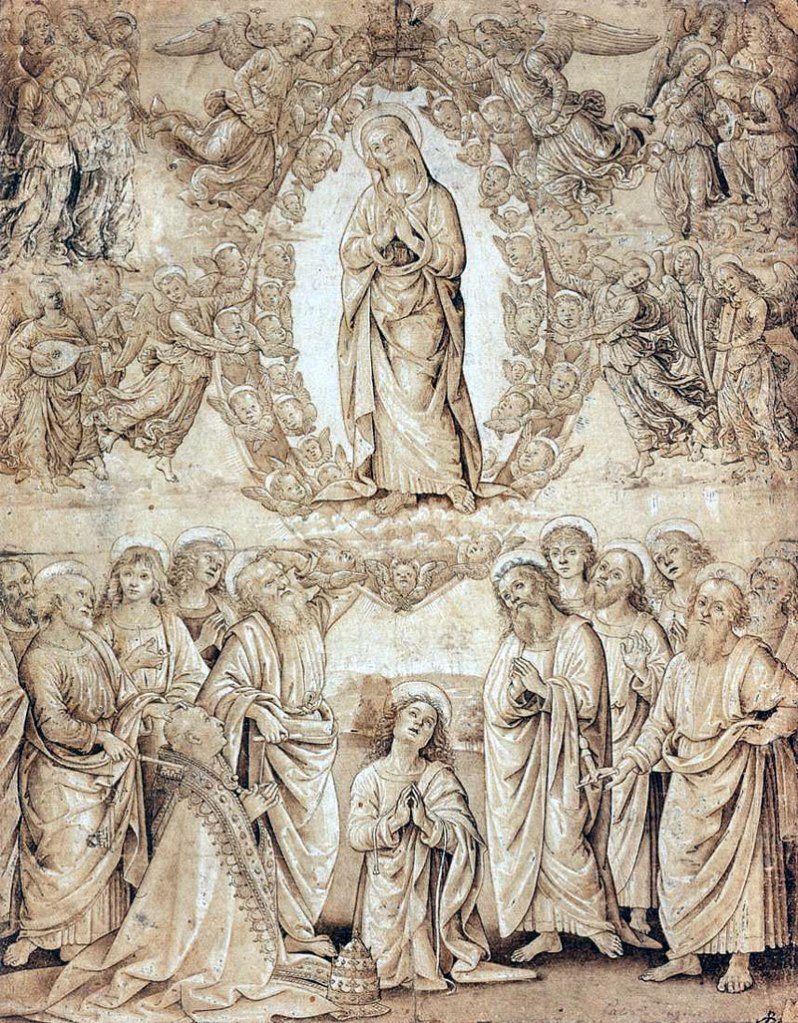

This figure represented as both a god of the sky and Pope Clement VII connects to the central figure in Botticelli’s Primavera representing the Assumption of the Virgin Mary into Heaven and to a lost fresco in the Sistine Chapel. The Chapel was dedicated to the Assumption of Mary by Pope Sixtus IV on her feast day of that name, August 15, 1483.

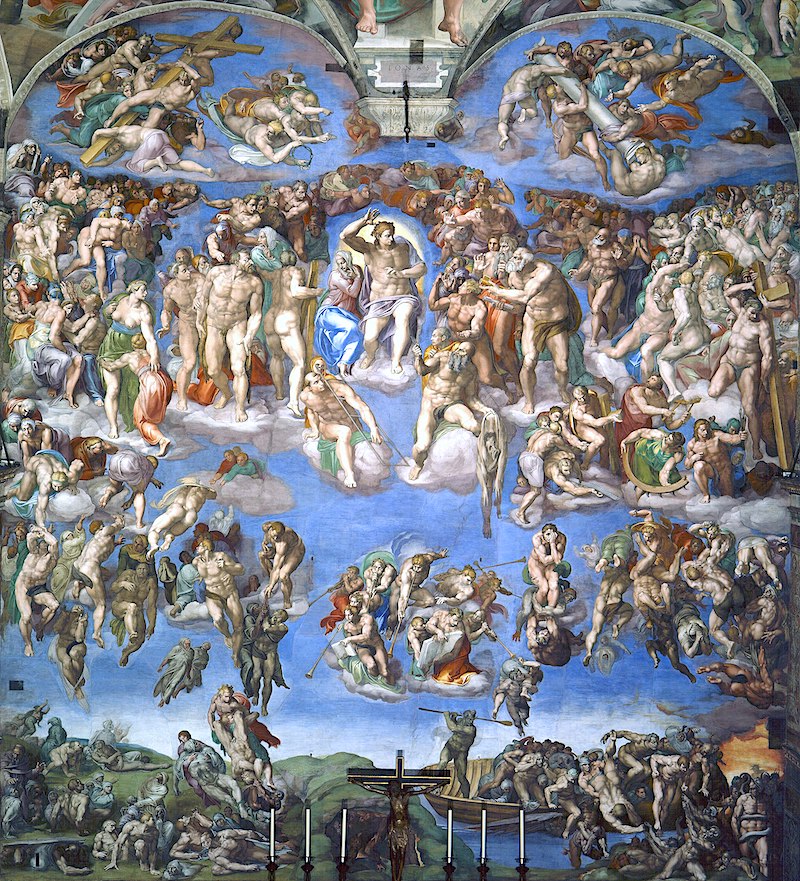

Covering the whole wall behind the altar in the Sistine Chapel is a fresco illustrating the Last Judgement, painted by Michelangelo between 1535 and 1541. However, the wall was originally frescoed by Pietro Perugino in the early 1480s depicting the Assumption of the Virgin.

It was Pope Clement VII who commissioned Michelangelo to overpaint or cover up Perugino’s Assumption fresco with the Last Judgment painting shortly before his death in September 1534, less than a year after attending the wedding of Catherine de’ Medici and Henry of Orleans at Marseille in France.

Grandes Chroniques de France, BnF, department of Manuscripts

The French connection introduces the anti-pope Clement VII (Robert of Geneva) who was elected pope in September 1378 by cardinals who opposed the return of the papacy from Avignon to Rome. His reign as anti-pope lasted until his death in September 1394, but what became known as the Papal Schism within the Catholic Church lasted until 1417. Robert of Geneva’s claim as pope was never recognised by the Church of Rome, hence Giulio de Medici taking the name Clement and listed as the legitimate Pope Clement VII. The irony is that Giulio himself was born illegitimate, the son of Fioretta Gorini. Illegitimacy is one of the themes iulioembedded in the Vasari fresco.

Giulio’s birth was legitimised with a papal dispensation issued by Pope Leo X in 1513 when it was declared that his parents, Giuliano de’ Medici and Fioretta had been “wed according to those present”. However, the declaration was made 35 years after Giulio was born and the witnesses were said to be two monks and a relation of Fioretta Gorini. Seemingly Fioretta had died by then and was not able to verify the witnesses evidence. So were the claims of the three witnesses legitimate?

Close inspection of Pope Clement VII’s red bonnet, shows it partially covering another. This reflects the suppression of Robert of Geneva’s false claim to the papacy. It also refers to the covering up of Perugino’s Assumption fresco that showed Pope Sixtus IV kneeling among the group of the Twelve Apostles. It is said that Sixtus instigated the Pazzi Conspiracy which resulted in the assassination of Giuliano de’ Medici, considered to be the father of Clement VII, hence the reason for the Medici pope wanting Michelangelo to cover the scene with a new fresco.

Sixtus IV also makes a connection to Jupiter. His birth name was Francesco della Rovere. Rovere translates as “oak”, and the oak tree was another symbol associated with Jupiter the “sky god”. Sixtus incorporated the oak tree in his papal arms. Arms and armour is another embedded them in the Vasari painting.

The iconography related to Clement I is the purse hanging from the side of the papal figure. Clement I was martyred by being thrown into the sea and weighed down by an anchor. He is usually portrayed with an anchor at his side. The purse feature relates to the anti-pope Clement VII, an ambitious and stubborn man who resorted to extortion and simony – “the act of selling church offices and roles or sacred things”. Simony relates to the account of Simon Magus (Acts of the Apostles), a magician whom the people considered a divine power and called Great (another connection to the Magnificat and its meaning of greatness as explained in the previous post).

Simon Magus offered the apostle Peter money to receive the power to be able to lay hands on people for them to receive the Holy Spirit. But Peter, who had ordained Clement I by laying hands on him, dismissed the offer of money by Simon Magus and said: “May your silver be lost forever, and you with it, for thinking that money could buy what God has given for nothing” (Acts 8 20). Then Simon, weighed down by guilt and fear, pleaded with Peter to pray for him.

Clement VII was not without his faults in a manner that drained the Vatican treasury. He assigned positions in the Church, titles, land and money, in favour of his Medici relatives. This also makes a connection to Simon Magus as a magician. Note the proximity of Catherine de’ Medici’s dark right hand to Clement’s purse. It is claimed that Catherine was a practitioner of the dark arts, who relied on soothsayers, seers, mystics and astrologers to forecast her own and family’s future.

But this juxtaposition of hand and purse is another piece of iconography adapted from Botticelli’s Primavera. With Pope Clement substituted for the figure of Mary’s assumption (Venus), Catherine is a replacement for the figure of Botticelli’s Flora dispensing flowers from her apron purse.

So now the four identities associated with the central figure in the marriage scene are:

Pope Clement VII (Giulio de’ Medici)

Anti-pope Clement VII (Robert of Geneva)

Pope Clement I (Clement of Rome)

Jupiter, son of Saturn and Ops

• I hope to continue posting information about this Vasari fresco when I can source a higher resolution digital image of the work. The low-res version available on the internet lacks important visual detail to explain clearly some of the narratives embedded by the artist. If anyone out there has access to a better-quality version than I have used so far for my posts on this subject, please contact me.

You must be logged in to post a comment.