I previously posted on these two images some three years ago without knowing at the time of their connection to the Mérode Altarpiece.

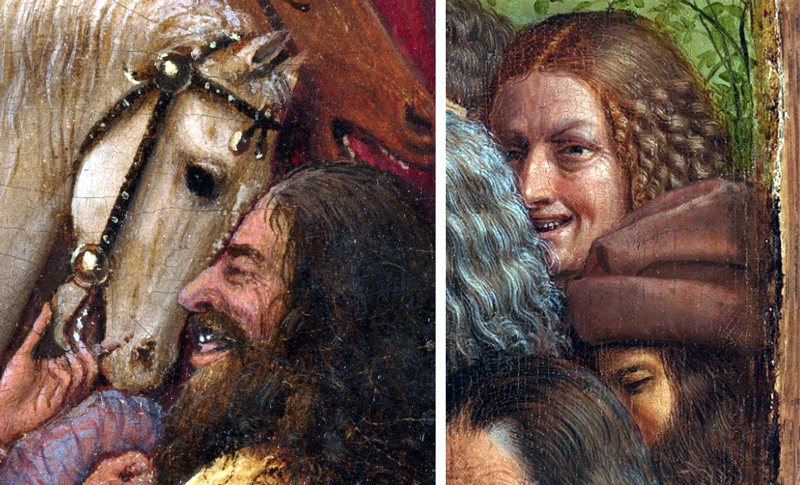

Left, is detail from the Crucifixion panel of the Crucifixion and Last Judgment diptych. Right, is detail from Pilgrims panel of the Ghent Altarpiece. Both are attributed to Jan Van Eyck.

The early commentaries are at these links:

Jankyn Van Eyck and the Wife of Bath

Eye for eye, tooth for tooth

The common detail in both images is teeth, and it is this reference that connects to the donor panel of the Mérode Altarpiece.

In a previous post – Of Temples and Teeth – I pointed out how the formation of crenels or merlons can be viewed as resembling teeth, and the indented formation also hints at a relationship or contract known as an indenture. I also added that the crenelation can be considered as referencing teeth as in the word comb, or Combe.

In another post – A Horn and a Hook – I published the Duchy of Cleves coat of arms. At the time, I didn’t pick up on the bull’s toothy smile, but it is yet another connection to the panel’s theme of teeth. Below are three versions of the crest, two of which are taken from the Hours of Catherine of Cleves. Notice the gap-toothed version.

Notice also that the woman’s red dress is ‘cleaved’ to reveal its white lining representing a row of teeth,

There’s more. The three buckles on the man’s purse are mouth-shaped with teeth. At another level and narrative they represent horseshoes and point to a third identity applied to the kneeling man, Arnold of Guelders (1410-1473), spouse of Catherine of Cleves (1417-1479).

Guelders, or Gelderland, is a Netherlands province famous for its mares that were bred to other bloodlines that eventually resulted in today’s breed of Gelderland horse.

The artist also punned Guelders to the Netherlands currency known as Guilders that was used from 1434 until 2002 when replaced by the euro, hence the buckles attached to the donor’s purse. The 1434 date may also give an indication to a period when the panel was painted.

Staying with the monetary theme, there are other narratives expressed by the shape of the three buckles attached to the purse, and which link to the identity of the kneeling man presented as the French theologian and philosopher, Jean Gerson.

The donor panel is embedded with several references to Gerson and his writings; the buckles on the purse are one example. They refer to a letter Gerson wrote to a benefactor requesting help in providing a source of income, and so a further connection to the purse. I shall outline the details in my next post.

Several features from the Mérode donor panel were adopted and adapted by Hugo van der Goes when he painted the St Vincent Panels.

You must be logged in to post a comment.