Simple answer: No. But they do bare their teeth.

In a letter to a benefactor requesting financial support, the French theologian and preacher Jean Gerson wrote: “The dolphins in their formations are harbingers of the storm, messengers of melancholy, most certain prophets of sorrow. Giving their tidings in wedge-shaped formation, alas, they come, bringing threats of cruel fate.”

There are various dates attributed to this early letter ranging from 1382 to 1390. But in 1393 Gerson’s fortunes took an upturn when he became almoner and confessor to Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, as well as receiving a benefice when he was appointed Dean of the collegiate church of St Donatian in Bruge.

The precincts of the church of St Donatian was where Jan Van Eyck was first laid to rest in 1441 before his body was later translated into the church and buried near the baptismal font.

The mention of dolphins in Gerson’s letter may have alluded to the dauphins of the French throne. When the French King Charles V died in 1380, his brother Philip the Bold became more active at the court of France and served as the dominant of four regents when Charles VI, his nephew, succeeded to the throne at the age of 11.

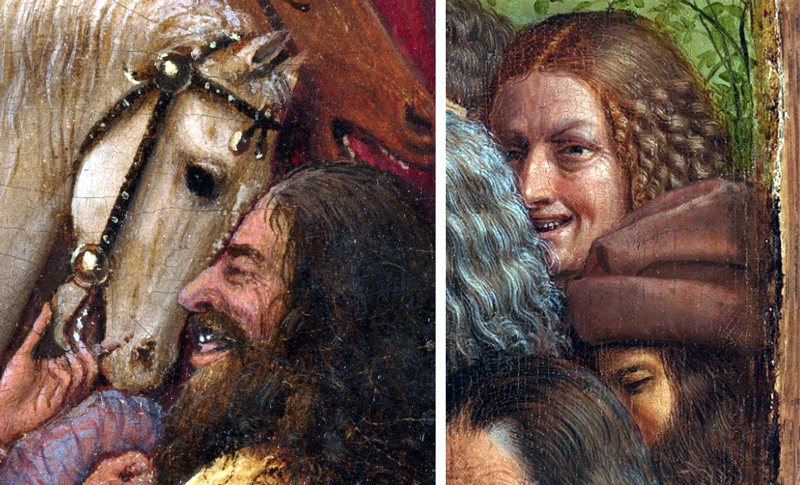

In the donor panel of the Mérode Altarpiece Philip the Bold, now Gerson’s patron, and the reference to dolphins, is visually embedded in an inspired fashion that includes a homophonic pun on the duke’s name Philip – Flip – as in the acrobatic fashion of dolphins, and its flipper limbs. So let’s flip an image published in my previous post, Gerson’s purse and its attached buckles, and examine it from a new perspective.

Now we are presented with the upper open jaws of three dolphins baring their teeth. The two larger mammals appears to have scrolls in their mouth, perhaps echoing the text in Gerson’s letter describing dolphins as messengers of melancholy and prophets of sorrow.

Various causes of melancholy or depression are often referred to in Gerson’s writings, and as a priest and preacher he could be described as a prophet of sorrow in calling and encouraging people to repent.

Philip was given the epithet “the Bold” when, as a fourteen-year-old, he fought bravely at the side of his father, the French king John, at the Battle of Poitiers. Both were taken captive at the battle on September 19, 1356, and brought to London where they remained for four years before a ransom was agreed and paid for their release.

• The information appertaining to Jean Gerson and his letter is sourced from the book Jean Gerson Early Works, translated and introduced by Brian Patrick McGuire, and published by Paulist Press, Mahwah, New Jersey.

You must be logged in to post a comment.